Fortuna

Fortuna (equivalent to the Greek goddess Tyche) was the goddess of fortune and personification of luck in Roman religion. She might bring good luck or bad: she could be represented as veiled and blind, as in modern depictions of Justice, and came to represent life's capriciousness. She was also a goddess of fate: as Atrox Fortuna, she claimed the young lives of the princeps Augustus' grandsons Gaius and Lucius, prospective heirs to the Empire.[1]

Her father was said to be Jupiter and like him, she could also be bountiful (Copia). As Annonaria she protected grain supplies. June 11 was sacred to her: on June 24 she was given cult at the festival of Fors Fortuna.[2][3]

Contents |

Cult

Fortuna's Roman cult was variously attributed to Servius Tullius – whose exceptional good fortune suggested their sexual intimacy[4] – and to Ancus Marcius.[5] She had a temple at the Forum Boarium and a sacred precinct on the Quirinalis as Fortuna Populi Romani (the Fortune of the Roman people). Her identity as personification of chance events was closely tied to virtus (strength of character). Public officials who lacked virtues invited ill-fortune on themselves and Rome: Sallust uses the infamous Catiline as illustration – "Truly, when in the place of work, idleness, in place of the spirit of measure and equity, caprice and pride invade, fortune is changed just as with morality".[6]

An oracle at the Temple of Fortuna Primigena in Praeneste used a form of divination in which a small boy picked out one of various futures that were written on oak rods. Cults to Fortuna in her many forms are attested throughout the Roman world. Dedications have been found to Fortuna Dubia (doubtful fortune), Fortuna Brevis (fickle or wayward fortune) and Fortuna Mala (bad fortune).

She is found in a variety of domestic and personal contexts. During the early Empire, an amulet from the House of Menander in Pompeii links her to the Egyptian goddess Isis, as Isis-Fortuna[7]. She is functionally related to the God Bonus Eventus[8], who is often represented as her counterpart: both appear on amulets and intaglio engraved gems across the Roman world.

Her name seems to derive from Vortumna (she who revolves the year): the earliest reference to the Wheel of Fortune, emblematic of the endless changes in life between prosperity and disaster, is 55 BCE.[9] In Seneca's tragedy Agamemnon, a chorus addresses Fortuna in terms that would remain almost proverbial, and in a high heroic ranting mode that Renaissance writers would emulate:

"O Fortune, who dost bestow the throne’s high boon with mocking hand, in dangerous and doubtful state thou settest the too exalted. Never have sceptres obtained calm peace or certain tenure; care on care weighs them down, and ever do fresh storms vex their souls. ...great kingdoms sink of their own weight, and Fortune gives way ‘neath the burden of herself. Sails swollen with favouring breezes fear blasts too strongly theirs; the tower which rears its head to the very clouds is beaten by rainy Auster.... Whatever Fortune has raised on high, she lifts but to bring low. Modest estate has longer life; then happy he whoe’er, content with the common lot, with safe breeze hugs the shore, and, fearing to trust his skiff to the wider sea, with unambitious oar keeps close to land."[10]

Ovid's description is typical of Roman representations: in a letter from exile[11] he reflects ruefully on the "goddess who admits by her unsteady wheel her own fickleness; she always has its apex beneath her swaying foot."

Middle Ages

Fortuna did not disappear from the popular imagination with the ascendancy of Christianity by any means.[12] Saint Augustine took a stand against her continuing presence, in the City of God: "How, therefore, is she good, who without discernment comes to both the good and to the bad? ...It profits one nothing to worship her if she is truly fortune... let the bad worship her...this supposed deity".[13] In the 6th century, the Consolation of Philosophy, by statesman and philosopher Boethius, written while he faced execution, reflected the Christian theology of casus, that the apparently random and often ruinous turns of Fortune's Wheel are in fact both inevitable and providential, that even the most coincidental events are part of God's hidden plan which one should not resist or try to change. Fortuna, then, was a servant of God,[14] and events, individual decisions, the influence of the stars were all merely vehicles of Divine Will. In succeeding generations Boethius' Consolation was required reading for scholars and students. Fortune crept back in to popular acceptance, with a new iconographic trait, "two-faced Fortune", Fortuna bifrons; such depictions continue into the 15th century.[15]

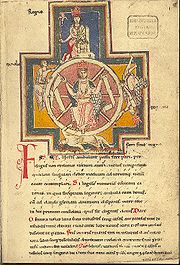

The ubiquitous image of the Wheel of Fortune found throughout the Middle Ages and beyond was a direct legacy of the second book of Boethius's Consolation. The Wheel appears in many renditions from tiny miniatures in manuscripts to huge stained glass windows in cathedrals, such as at Amiens. Lady Fortune is usually represented as larger than life to underscore her importance. The wheel characteristically has four shelves, or stages of life, with four human figures, usually labeled on the left regnabo (I shall reign), on the top regno (I reign) and is usually crowned, descending on the right regnavi (I have reigned) and the lowly figure on the bottom is marked sum sine regno (I have no kingdom). Medieval representations of Fortune emphasize her duality and instability, such as two faces side by side like Janus; one face smiling the other frowning; half the face white the other black; she may be blindfolded but without scales, blind to justice. She was associated with the cornucopia, ship's rudder, the ball and the wheel. The cornucopia is where plenty flows from, the Helmsman's rudder steers fate, the globe symbolizes chance (who gets good or bad luck), and the wheel symbolizes that luck, good or bad, never lasts.

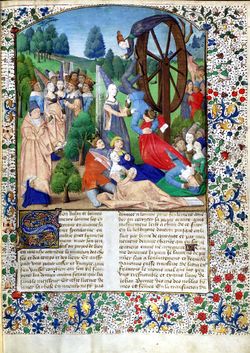

Fortune would have many influences in cultural works throughout the Middle Ages. In Le Roman de la Rose, Fortune frustrates the hopes of a lover who has been helped by a personified character "Reason". In Dante's Inferno (vii.67-96) Virgil explains the nature of Fortune, both a devil and a ministring angel, subservient to God. Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium ("The Fortunes of Famous Men"), used by John Lydgate to compose his Fall of Princes, tells of many where the turn of Fortune's wheel brought those most high to disaster, and Boccaccio essay De remedii dell'una e dell'altra Fortuna, depends upon Boethius for the double nature of Fortuna. Fortune makes her appearance in Carmina Burana (see image). The Christianized Lady Fortune is not autonomous: illustrations for Boccaccio's Remedii show Fortuna enthroned in a triumphal car with reins that lead to heaven,[16] and appears in chapter 25 of Machiavelli's The Prince, in which he says Fortune only rules one half of men's fate, the other half being of their own will. Machiavelli reminds the reader that Fortune is a woman, that she favours a strong, or even violent hand, and that she favours the more aggressive and bold young man than a timid elder. Even Shakespeare was no stranger to Lady Fortune:

- When in disgrace with Fortune and men's eyes

- I all alone beweep my outcast state ... — Sonnet 29

Pars Fortuna in Astrology

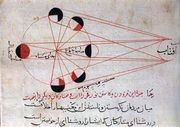

In Astrology the term ‘Pars Fortuna’ represents a mathematical point in the zodiac derived by the longitudinal positions of the Sun, Moon and Ascendant (Rising sign) in the birth chart of an individual. It represents an especially beneficial point in the horoscopic chart. In Arabic Astrology, this point is called Arabian Parts.[17]

The procedure followed for fixing one’s Pars Fortuna in ancient and traditional astrology depended on the time of birth, viz., during daylight or night time (whether the Sun was above or below the horizon). In modern western astrology the day time formula only was used for many years, but with more knowledge of ancient astrology, the two calculation method is now often used.

The formula for calculating the day time Part of Fortune (PF) is (using the 360 degree positions for each point):

The formula for the night-time Part of Fortune is PF = Ascendant + Sun - Moon

Each calculation method results in a different zodiac position for the Part of Fortune.[18]

Al Biruni (973 – 1048), an 11th-century mathematician, astronomer and scholar, who was the greatest proponent of this system of prediction, listed a total of 97 Arabic Parts, which were widely used for astrological consultations. Paul Vachier has prepared an Arabic Parts Calculator for all the Arabic Parts. [19]

Aspects of Fortuna

- Fortuna Annonaria brought the luck of the harvest

- Fortuna Belli the fortune of war

- Fortuna Primigenia directed the fortune of a firstborn child at the moment of birth

- Fortuna Virilis attended a man's career

- Fortuna Redux brought one safely home

- Fortuna Respiciens the fortune of the provider

- Fortuna Muliebris the luck of a woman. Typical of Roman attitudes, the fortune of a woman in marriage, however, was Fortuna Virilis.

- Fortuna Victrix brought victory in battle

- Fortuna Conservatrix the fortune of the Preserver [21]

- Fortuna Equestris fortune of the Knights [21].

- Fortuna Huiusque fortune of the present day[21].

- Fortuna Obsequens fortune of indulgence[21].

- Fortuna Privata fortune of the private individual[21].

- Fortuna Publica fortune of the people[21].

- Fortuna Romana fortune of Rome[21].

- Fortuna Virgo fortune of the virgin [21].

- Pars Fortuna[22]

See also

- The Wheel of Fortune

- Fortune favours the bold

- Carmina Burana (Orff) (opening theme: O Fortuna)

- Goth's Column

Notes

- ↑ Marguerite Kretschmer, "Atrox Fortuna" The Classical Journal 22.4 (January 1927), 267 - 275.

- ↑ Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome,; (London: Oxford University Press) 1929: on-line text.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti VI. 773‑786.

- ↑ Varro, De Lingua Latina VI.17.

- ↑ Plutarch; see Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome,; (London: Oxford University Press) 1929: on-line text.

- ↑ Verum ubi pro labore desidia, pro continentia et aequitate lubido atque superbia invasere, fortuna simul cum moribus immutatur, Sallust, Catilina, ii.5. His view of fortuna is discussed in Etienne Tiffou, "Salluste et la Fortuna", Phoenix, 31.4 (Winter 1977), 349 - 360.

- ↑ Allison, P., 2006, The Insula of Menander at Pompeii: Vol.III, The Finds; A Contextual Study, Oxford: Claredon Press

- ↑ Greene, E.M., “The Intaglios”, in Birley, A. and Blake, J., 2005, Vindolanda: The Excavations of 2003-2004, Bardon Mill: Vindolanda Trust, pp187-193

- ↑ Cicero, In Pisonem.

- ↑ Agamemnon, translation by Frank Justus Miller (on-line text)

- ↑ Ovid, Ex Ponto, iv, epistle 3.

- ↑ Howard R. Patch, The Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Literature, 1927 is the basic study.

- ↑ Augustine, City of God, iv.18-18; v.8.

- ↑ Selma Pfeiffenberger, "Notes on the Iconology of Donatello's Judgment of Pilate at San Lorenzo" Renaissance Quarterly 20.4 (Winter 1967:437-454) p 440.

- ↑ As Pfeiffenberger observes, citing A. Laborde, Les manuscrits à peintures de la Cité de Dieu, Paris, 1909: vol. III, pls 59, 65; Pfeiffenberger notes that there are no depictions of a Fortuna bifrons in Roman art.

- ↑ Noted by Pfeiffenberger 1967:441.

- ↑ -Part of Fortune; David Plant, "Fortune, Spirit and the Lunation Cycle"

- ↑ David Plant, op. cit..

- ↑ Paul Vachier, "Arabic Parts".

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 http://www.thaliatook.com/OGOD/augusta.html Augusta

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 http://www.mlahanas.de/RomanEmpire/Mythology/Fortuna.html Fortuna

- ↑ Arabic Parts

References

- David Plant, "Fortune, Spirit and the Lunation Cycle"

- www.cafeastrology.com Part of Fortune

- Howard Rollin Patch (1923), Fortuna in Old French Literature

- Lesley Adkins, Roy A. Adkins (2001) Dictionary of Roman Religion

- Howard Rollin Patch (1927, repr. 1967), The Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Literature

- Howard Rollin Patch (1922), The Tradition of the Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Philosophy and Literature

External links

- Michael Best, "Medieval tragedy"

- Arya, Darius Andre (January 27 2006) [2002] (PDF). The Goddess Fortuna in Imperial Rome: Cult, Art, Text. Theses and Dissertations from The University of Texas at Austin. Austin: University of Texas at Austin. http://hdl.handle.net/2152/152. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||